If nitrogen deficiencies can prove to be the cause of dangerous fermentations, these low levels also have advantages in terms of controlling fermentation and aromas.

THE DANGER OF UNCOMPENSATED DEFICIENCIES

The part of nitrogen, which can be assimilated by yeast, is made up of what is known as organic (or aminic); this comprises all the amino acids except proline, but also mineral (or ammoniacal) nitrogen, represented by the ammonium ion NH4+. It is often held that musts contain on average two-thirds free amino nitrogen and one-third ammoniacal nitrogen, but in fact, there can be great disparity in the ratio of amino/ammoniacal nitrogen depending on the batch and the vintage.

When we can use the term ‘deficiency’?

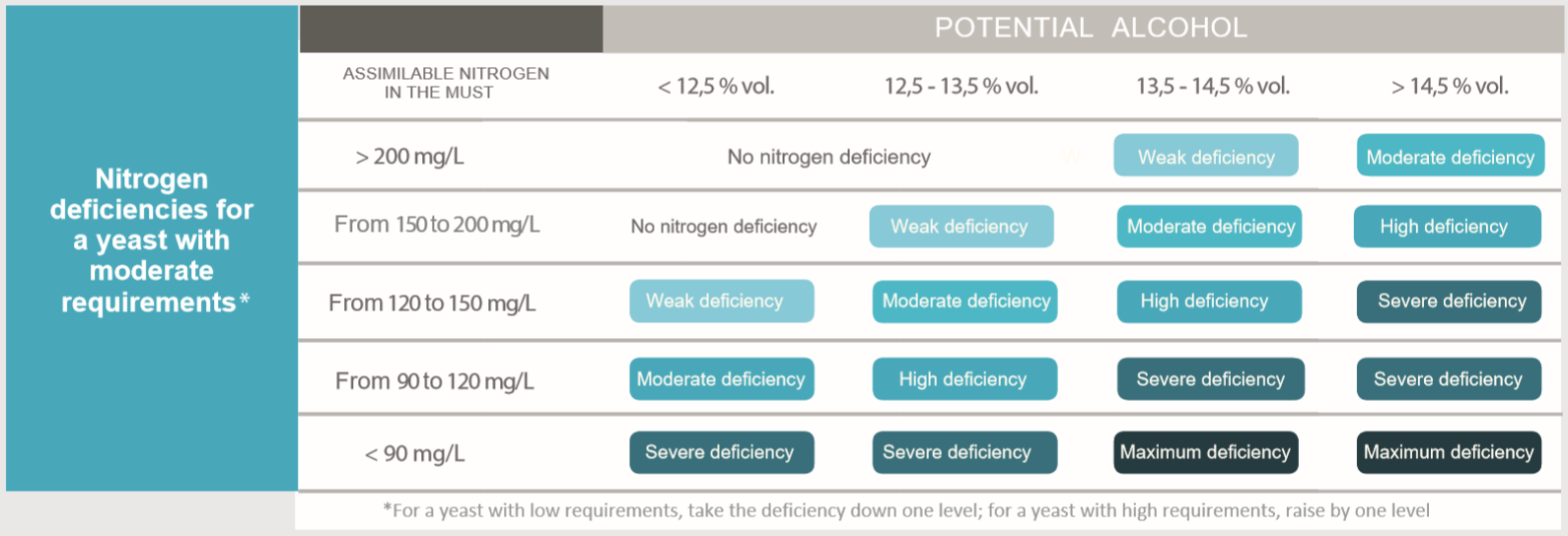

Yeasts with moderate nitrogen requirements need around 150 mg/l of assimilable nitrogen in order to correctly start an alcoholic fermentation (FA). Depending on the amount of sugar to ferment, this need can increase drastically. In addition, some yeasts are a little less demanding, others much more. Lastly, factors such as low pH (<3.1), or “extreme” temperatures (<14 ° C or> 28 ° C) increase the nitrogen requirements of yeasts.

Consequences of nitrogen deficiency

- Insufficient multiplication of yeasts to complete AF.

- Yeasts produce H2S and give off a sulphurous smell known as “flattening”.

- Proteins produced with a membrane unable to allow sugars to be correctly integrated or to fully develop the aromatic potential of the grapes in the yeast.

- Scarcity of amino acids (aroma precursors) and less expressive wines.

- Difficulties with malolactic fermentation because of the bacteria’s amino-acid requirements.

LOW NITROGEN LEVELS: GREAT FOR KEEPING CONTROL OVER VINIFICATION

It may sound paradoxical, but at times, it is better to have a lack of nitrogen in the must than an over-abundance, since the former case can be corrected but the latter cannot: excess nitrogen cannot be eliminated and may lead to equally disastrous consequences.

Halt the overpopulation of yeasts

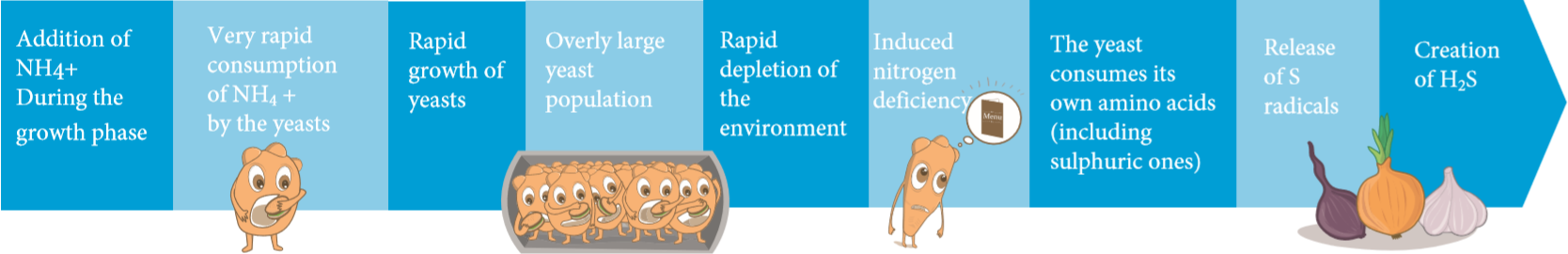

Any excess ammoniacal nitrogen during the growth stage (i.e. up to 1/3 of the way through AF) will be assimilated too quickly by the multiplying yeast. The result is a spike in the yeast population, and an oversized, depleted biomass, which will continue to absorb the nutrients containing nitrogen, vitamins and minerals in the must. The deficiency arising from this will then lead to the creation of damaging sulphur smells.

If ammoniacal nitrogen is added to a must in this state, the situation risks deteriorating and creating the conditions for further yeast growth.

Keeping nitrogen in balance

An initial deficiency in the must presents some great opportunities, as the winemaker does not have to worry about excess ammoniacal nitrogen being created and can correct the nitrogen deficit by adding amino acids. The organic nitrogen is then assimilated much more slowly and evenly by the yeasts than ammoniacal nitrogen would be. There is no overpopulation of yeasts and the yeasts’ nitrogen requirements are met.

A situation also allowing the winemaker to fine-tune the sensory profile

Excess ammoniacal nitrogen inhibits the synthesis of certain aromas. Subileau et al. have shown that ammonia can negatively affect the entrance of the precursors to the varietal thiols into the yeast, leading to lower concentrations of minor fruity thiols in these wines. The R&D department at IOC has confirmed this observation and demonstrated that using a 100% amino-acid source of nitrogen leads to the production of wines with greater concentrations of fruity thiols and positive aromas on the ester front.

How can these deficiencies be handled from day to day?

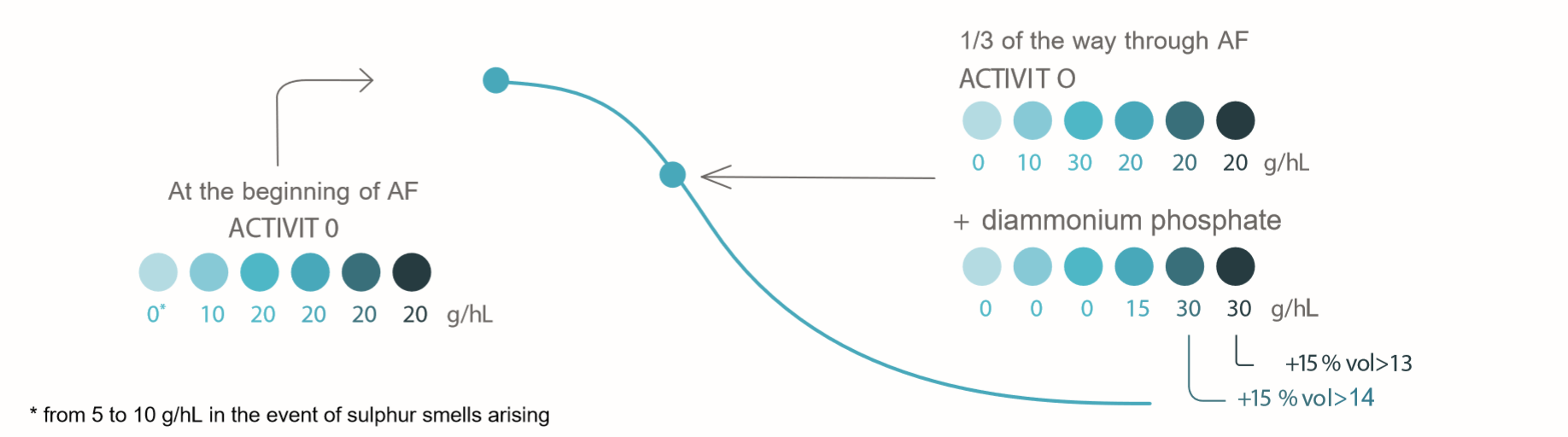

IOC has developed a yeast autolysate with an extraordinarily high amount of assimilable and bioavailable amino acids. Coupled with thiamine, it forms ACTIVIT O, a nutrient designed to bring situations of deficiency (including vitamin and mineral deficiency) back into balance without affecting the sensory qualities of the wine.

In order to optimise the supplementation, you need to first know the initial level of deficiency:

The next step is to use the dosages and stick to the recommended times for each level of deficiency:

Example: in the event of a severe deficiency in a must with a potential alcohol content of 15.3% vol., you need to add:

- 20 g/hl ACTIVIT 0 at the beginning of AF;

- 20 g/hl ACTIVIT 0 and 45 g/hl of diammonium phosphate 1/3 of the way through AF.

Based on what has just been said, it doesn’t take much to realize that it’s a good idea to perform analyses of assimilable nitrogen on the various musts being made ready for fermentation in order to adapt the nutritional program and fill these harmful deficiencies, turning a risk into… opportunity!